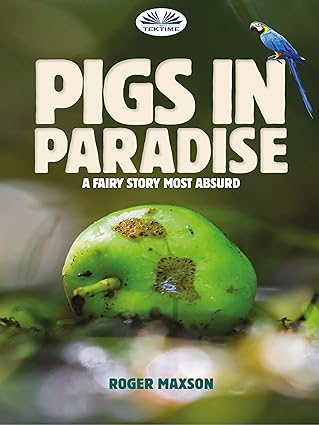

When Fox News sends a crew halfway around the world to report on a cow that gave birth in Israel, the new calf must be something spectacular, or at least something likely to increase ratings and fan some flames. Indeed, Lizzy is special, a miracle heifer by many accounts. This red calf born to a Jersey cow grabs the ardent attention of Jews, Muslims, Christians, and superstitious parties the world over. The birth is praised as a milestone pointing toward a glorious new dawn, and devout animals in the barn revel in the event. But not every animal reckons Lizzy’s arrival an auspicious event. The calf’s mother dislikes the frenzied attention, the neighbors on the other side of the fence abhor the entire spectacle, and Julius, a cheeky barn parrot, isn’t given to such mindless devotion. His take is that all the fuss amounts to an absurd fairy tale with a less-than-happy ending. And he isn’t far off. One character sees a vision of things to come as the evangelicals are en route. “They will offer us salvation and paradise on earth, but what they want is to enslave us once again to the yoke and worse.” The animals are carted off and the evangelicals hold sway over the melee, animal and human alike.

Structurally similar to Orwell’s iconic Animal Farm, Roger Maxson shifts the scathing denunciation from communism to religionism in Pigs In Paradise: A Fairy Story Most Absurd. Among the many parallels, there is ample symbolism, a clear hierarchy among the animals, and commandments that are divisive and easily manipulated for selfish gain. The novel has the tone of an outrageous, impassioned Bible parody, and that’s true even before human characters influence the plot. Humor comes in myriad ways, from a mule cast as a priest to parrots unable to keep secrets. Even the book’s ironic cover is a punchline. Prickly political topics also play a part in the story arc, starting with the farm animals who live on a moshav to the ridiculous marriage of church and state. While scenes of prolific dialogue make it challenging to get to know the characters beyond their exaggerated stereotypes, these generalities effectively belittle the zealots while revealing their exploitation. The author’s rallying cry against religion is as doggedly fanatic as the organizations he rails against, but this will unquestionably appeal to readers who have seen the hypocrisy and cruelty perpetrated by religious fanaticism. More vitriol than vim, Pigs In Paradise isn’t likely to change many minds, but its undeniably powerful satire is certain to land well with like-minded audiences.